The Lantern

“He stood 5’5” but walked like he was 6’4””

Written by: Mikeie Honda Reiland

Illustrations by: Andrew Gragg

People in Nashville say Rasheed Walker was a lantern. He could illuminate dark areas, create light where none existed. But before he could light up his hometown, before he could realize all his potential, he lay broken on a gurney on the 10th floor of Vanderbilt Hospital.

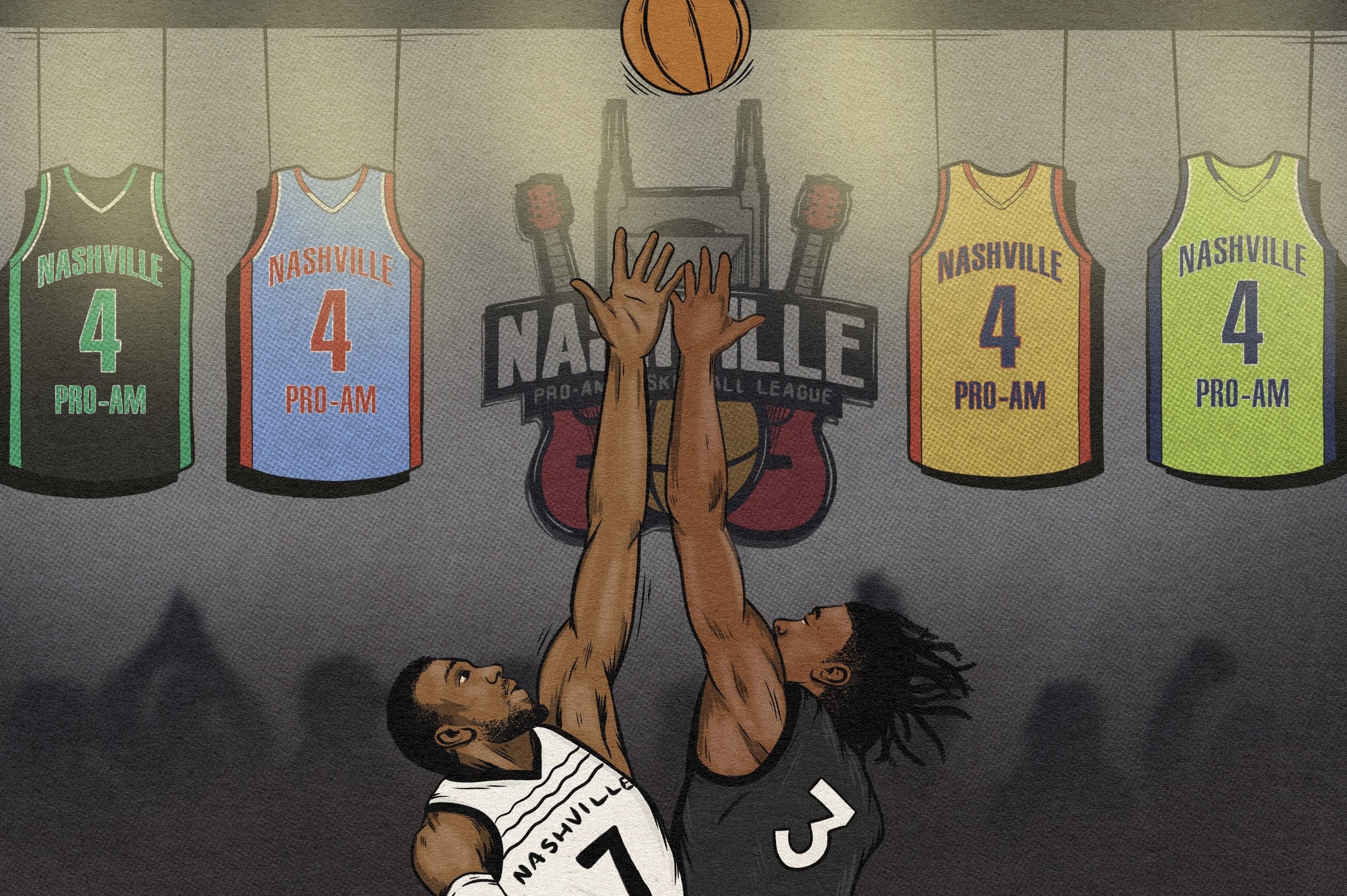

Bringing the Pro-Am back was one of Rasheed’s big dreams, the big something that everyone expected from him.

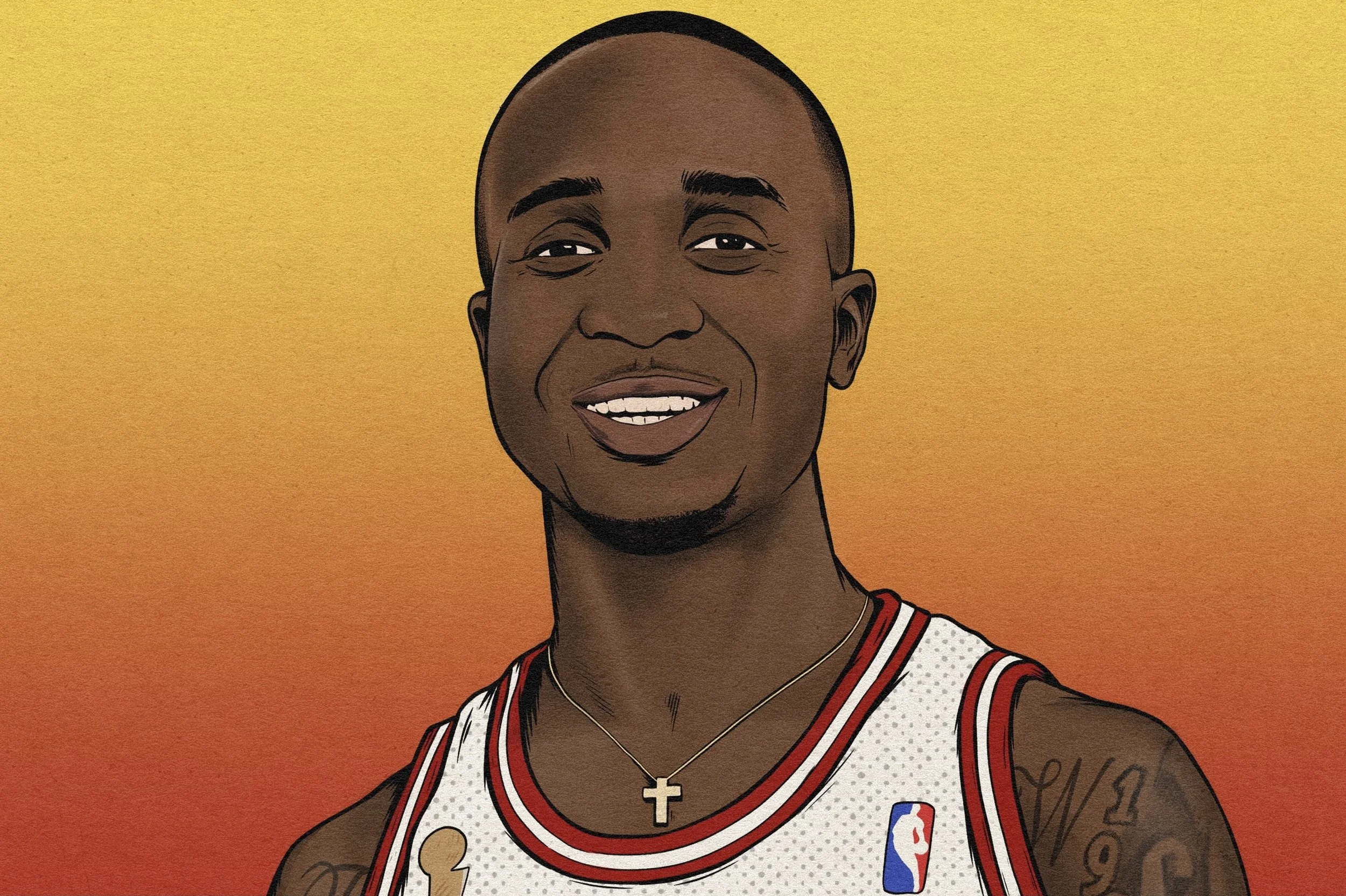

Normally, Rasheed moved through space like he was aware of people perceiving him, like he knew he was always on someone’s stage. He stood 5’5” but walked like he was 6’4”. Pacing the sidelines at basketball games, he wore a silver cross at his chest, technicolor silicone bands and an icy watch at his wrists. A buzzcut topped his high forehead, and his arms, often visible beneath a throwback basketball jersey, were ropy and muscular. Even in his late twenties, Rasheed looked like he'd have a tough time growing a decent beard. Corisa hated tattoos, but her son had her name and Benny's name inked across his arms, Marvin the Martian and Batman and a Black Power fist on his legs. His nickname at the Antioch Steak n' Shake, where he line cooked as a teenager, was José Hustle.

Lying there in the hospital, Rasheed was 27, and looked much older. He was broken. But his energy was unmistakable.

“We gonna do the league this year?” He said.

“Absolutely,” Jeff replied.

“Absolutely we’re gonna do it.”

In the weeks to come, as he gritted through physical therapy in a rehab hospital, Rasheed couldn’t help feeling alone. Corisa and Benny remained at his side. But no one could do the work except him. The plans he’d harbored since he was a kid faced off against loneliness and the possibility he’d never walk again. Rasheed Walker, mid-twenties Golden Boy, versus a quarter-life crisis

Rasheed resolved that the crash wouldn’t break him. When rehab got tough, when he struggled to walk, he thought of the Pro-Am and the kids in his community.

“What kept me motivated was fulfilling the rest of my dreams,” he said. “I needed to get healthy again so I could continue living. A lot of people were counting on me and looked up to me.”

So Rasheed bought all the way in to physical therapy. He nicknamed himself “Triple R,” for “Rapid Recovery Rasheed.” The crash showed him that nothing was guaranteed. If he wanted to become the person he was supposed to be, the time was now.

On a Friday night in March 2016, after a week of teaching math at Whites Creek High, Rasheed went out to a concert with friends. Driving home, he missed his offramp, so he took the next exit. It was the darkest part of the night, and he couldn’t make out the signs. He swung his car around, turned onto what he thought was an onramp, and slammed into an onrushing car. The force of the crash tossed him from his white sedan, and he landed, hard, on the asphalt. The other driver wasn’t seriously injured.

Every bone in Rasheed’s face, along with his ankle and collarbone, shattered. His intestines ruptured. In the Vanderbilt ER, doctors figured he had a 20% chance to survive. In the early hours of that Saturday morning, they wheeled him into the operating room to fix his stomach. Over the next four days, Rasheed endured seven more surgeries.

Once he could see visitors, it felt like everyone from his past filtered through his hospital room. In his community, in the outer areas just north of Nashville – the city where his family had lived for a long, long time – almost everyone knew Rasheed. He carried an air of Chosen One assuredness. He traveled to Chicago and always had money in his pocket. He earned two bachelor’s degrees from Tuskegee, and his charisma seemed to get him whatever he wanted in life. Of all the city’s middle-class kids with big notions, he was the one who was going to make it.

Like many ‘90s babies, he grew up loving Space Jam, Jordans, the Chicago Bulls, and the Dallas Cowboys. Rasheed told anyone who listened that he wanted to be Jerry Maguire. That hadn’t happened – yet. He was teaching math as a long-term substitute at a local high school. But it didn’t seem all that crazy that Rasheed could become a sports agent. In the spring of 2016, he appeared on the cusp of something big

One day, lying in the hospital, Rasheed received a visit from Jeff McGruder, a local banker and grassroots basketball leader. A month earlier, the two had sat in Jeff’s suburban living room and, over Yazoo Pale Ales, created a plan to re-launch Nashville’s Pro-Am Basketball League. Jeff had written a business plan for a league a few years earlier, but he’d never had the time to make it happen. One of Jeff’s fraternity brothers connected him with Rasheed.

In its heyday, when Jeff was in high school, the Pro-Am provided an outlet for young Nashvillians who didn’t have much else going on.

“But his appetite had disappeared. It seemed like his physical essence had been stripped away, like only the casing remained. ”

Rasheed spent 39 days in the Vanderbilt ER, the trauma ICU, and the rehab hospital, where, with the help of a physical therapist, he learned to walk again. During those 39 days, Corisa lived in Rasheed’s room and in various hospital lobbies, reading her son his favorite Bible verses as he fell asleep.

By the time he returned home in April, after nine surgeries, Rasheed’s muscular frame had grown thin and willowy. He was usually a healthy, hearty eater; his meal of choice was a turkey sandwich and an apple at Panera. But his appetite had disappeared. It seemed like his physical essence had been stripped away, like only the casing remained.

Slowly, gradually, Rasheed regained his energy. For the rest of that spring, as he rebuilt himself, he and Jeff reimagined the Pro-Am. They did most of their work over text message, looking for sponsors, players, and a venue.

“He was scrawny, man,” Jeff says. “Scrawwwwny. Head full of hair, looked really bad. Didn’t look like himself. But man, he worked his butt off, trained, got back in shape, and we were off and running.”

To receive donations from businesses and apply for nonprofit status, they created a foundation called HUSTLEStrong. The nickname and the ethos had stuck with Rasheed ever since his Steak n’ Shake days. “Hustle” became a personal mantra and an acronym, especially after the crash. It stood for “How U Survive Through Life Everyday.”

Jeff knew what it was like to face adversity, though his arrived in a different package than Rasheed’s. Like Rasheed, his family is old Nashville. As a kid, he bounced between family houses in East and North Nashville, both historic Black hubs of the city. But while Rasheed grew up comfortably, Jeff’s mother spent time in prison.

“In the ‘40s, jazz, blues, and rock had rolled out the doors of clubs that dotted that road.”

When he fell asleep at his grandparents’ house on North 32nd, Jeff could hear the marching bands play at Tennessee State and Fisk University, the schools where his father had once played basketball, the historically Black colleges and universities near Jefferson Street. In the ‘40s, jazz, blues, and rock had rolled out the doors of clubs that dotted that road. Ray Charles, Jimi Hendrix, and Otis Redding all played shows along Jefferson. But in the ‘60s, the city faced a choice: Build I-40 near Belle Meade and Vanderbilt University, historic centers of antebellum wealth. Or build I-40 through Jefferson Street, the Black part of town.

The new interstate decimated Jefferson Street and North Nashville, destroying 100 square blocks, including 16 blocks of businesses. It bisected Meharry Medical College, another historically Black school, and Fisk. The neighborhood crumbled, and it was in this diminished North Nashville where Jeff was raised in the ‘80s.

In his community and school, he saw the effects of disinvestment, poverty, and resulting hatred firsthand. Gangs like the Bottom Boys and South Six recruited at Stratford High, Jeff’s east side alma mater. But Jeff was an honors student, an Eagle Scout, a star shooting guard on the basketball team. He was insulated, off-limits.

A decade later, about 10 miles north of Jefferson Street, Rasheed grew up more comfortably in Madison. During the summers, he traveled with his Uncle Cedric’s business, the UniverSoul Circus of Atlanta, and worked as a junior usher.

When he was 11, the circus performed in South Africa. Rasheed met Winnie Mandela and, for the first time, saw big international cities and foreign shores. But what stuck with him most was a trip to Soweto, the area just outside Johannesburg created by apartheid. Amid tin walls and cardboard roofs and torn clothing hung upon lines like prayer flags, Rasheed met kids without shoes, families who cooked dinner with batteries, elders who carried water across muddy roads.

Many of these people looked like Rasheed. But he owned multiple pairs of Jordans. He had two loving parents, running water, and a full stomach. For the first time, he realized he had certain luxuries that many people didn’t. Even some people in his hometown.

“They’d done all the little things. All that was left to do was open the doors and see who showed up. ”

Before they left South Africa, Rasheed and his cousins left their clothes with a few kids in Soweto. And Rasheed returned to Nashville with a broader sense of himself and the world.

Because of their backgrounds and shared histories, Rasheed and Jeff both dreamed of lifting up Nashville youth and reinvigorating the city’s Black-owned businesses. A former teammate of Jeff’s had become the head basketball coach at Stratford, so the Pro-Am would be able to play in the school gym. They found sponsors like Slim n’ Husky’s, a pizza and beer joint on Buchanan Street, the north side’s new “Black Broadway.” Rasheed hired his friend Quael, a local DJ, entrepreneur, and former Tennessee State cornerback, to narrate the action on the floor.

As summertime drew nearer, Rasheed grew closer to full strength. He and Jeff had found a venue and sponsors. They’d done all the little things. All that was left to do was open the doors and see who showed up.

Rasheed dedicated his summers to the Pro-Am, but during the school year, he assumed an alter ego. He took a job as a long-term sub at Cora Howe School, a special-ed focused public school that enrolls kids from across the city.

Most of Cora Howe’s teachers don’t leave until they retire. They’re family, forged by years in the exceptional ed trenches. Many used to work at schools where the special ed classrooms were stuffed into a basement or attic. Here, they’re all special ed teachers, all fighting the same battle.

For the teachers and staff, each day presents something new. You might hear hushed hallways on days when students travel to work sites in the community. You might see two adults carry a thrashing kid out of a classroom, feet hovering off the ground. You might see a table get flipped. You will almost certainly see a beautiful interaction between a student and a teacher.

Cora Howe serves kids from the Sowetos of Nashville, kids with the opposite of a head start. It was a natural fit for Rasheed.

It was also his legacy, his inheritance. While Rasheed attended Gateway Elementary in Madison, Corisa worked a few miles away at Cora Howe, which had just opened. When Cora Howe moved into a newer, much nicer building in the heart of East Nashville, Rasheed was in middle school, and Corisa started bringing him along to meet her co-workers.

“Rasheed was probably 13 when I met him,” says K.C. Winfrey, then a teacher, now the principal. “I always thought he was the coolest kid. He was all about going into sports, and he was gonna be a sports agent, and all this cool, wonderful, grandiose stuff.”

Stories of Corisa’s kindness are legion at Cora Howe. Every Christmas, she gives a present to every single teacher and student. Each Valentine’s Day, she gives a present to every single teacher and student. Before the pandemic, she was organizing a prom.

In the spring of 2018, K.C.’s grandmother died, and he drove back to his hometown in Kentucky to be with his relatives. At the visitation at his family’s tiny church, just as the service was about to begin, the back door opened, and in walked Corisa.

“You have to look for my hometown,” K.C. says. “It’s in the middle of nowhere. But I remember seeing Corisa (walk in) and being like, ‘Of course Corisa came to my grandmother’s funeral.’ Because that’s just the kind of person she is.”

Corisa loves clothes, especially shoes, and she'll pair entire business casual outfits with suede, leopard print flats. She believes in the power of inspirational quotes. She has printed out dozens of them, one per page, and taped them up all over the walls of her restorative space at Cora Howe. Each year, the fire marshal tells K.C. that the quotes are a fire hazard. But he’d never tell Corisa to take them down.

Corisa, at barely five feet tall, barely ever raises her voice, but she commands so much respect that even her friends, even her elders, even her bosses call her “Ms. Corisa.”

Most twenty-somethings wouldn’t want to work in the same place as their mother. But Rasheed did. Wherever he went, he carried his mother with him. He was born Rasheed Cori Walker – Cori, as in Corisa. She and Benny split when Rasheed was young, but they stayed on good terms and teamed up to raise their son. Benny had children from a previous marriage, but Rasheed was Corisa’s only child, and she treasured him.

“If the kids needed lunch money, he gave them lunch money. If they needed discipline, he instilled it. If their brothers or fathers were absent, he provided a role model.”

Each morning, Rasheed took his coffee in Corisa’s room, where he kept some K-cup pods. Every afternoon, he returned to eat lunch with her. Each year, in the hallways, Rasheed and Corisa made gift bags for patients in the Vanderbilt ICU. He never forgot the doctors, surgeons, and nurses who saved him.

“They were as close as a mom and son could ever be,” K.C. says. “Rasheed was one half of Corisa’s heart. He put Corisa on a pedestal, and vice versa. They both held each other in the highest esteem.”

Rasheed taught a work-based learning group, going out to farms, restaurants, and nonprofits during the daytime. The group consisted mostly of boys, to whom he imparted his particular brand of masculinity. One fall, he and his class smashed pumpkins in the school’s backyard, finding a healthy outlet for their aggression. In his navy blue, long-sleeved Dallas Cowboys t-shirt, Rasheed stood with perfect posture, hands behind his back, alternating between yelps and grunts as his kids whaled on their gourds with the business ends of their shovels.

If the kids needed lunch money, he gave them lunch money. If they needed discipline, he instilled it. If their brothers or fathers were absent, he provided a role model.

“You can move beyond your circumstances,” he told them. “You’re frustrated now. You’re in special day school. Your life isn’t giving you the hand you think you deserve. But this doesn’t have to be your life. You can rise above it.”

“They created their own secret handshake, and Rasheed relied on his own, even-keeled way of communicating to bond with Jake. ”

He taught one student, Jake, who was non-verbal. None of the other teachers could get through to Jake. When Jake sensed irritation or escalated emotions, he rose to match them. But Rasheed could talk to him. They created their own secret handshake, and Rasheed relied on his own, even-keeled way of communicating to bond with Jake.

“I’ve been doing this work with behavioral science and kids my whole life, and I had a difficult time making a connection with Jake,” K.C. says. “But Rasheed and Jake were boys, man. It was special.”

There was another student, Jeremiah, whom the staff struggled to reach. Jeremiah dealt with autism, and his parents weren’t around, so his grandmother raised him. He kept getting in trouble at school. When he joined Rasheed’s classroom in 11th grade, his behavior completely changed. He often commented on Rasheed’s clothes, saying how much he liked them.

So one Christmas, after Jeremiah behaved well for a few months, Rasheed left a box with Corisa. It was a gift for Jeremiah, Rasheed told her. When Jeremiah tore open the present, he found a tracksuit, socks, and a pair of Jordans. He was so excited that he started to change clothes right away, stripping down in the middle of Corisa’s room.

“No, Jeremiah!” She said, trying not to laugh. “Go to the bathroom!”

When the kids behaved well, they earned Fun Fridays, during which they played flag football behind the school, students vs. teachers. In a school where teaching wasn’t easy, these football games offered the adults a chance to enforce hierarchy, to demonstrate who ran things. The teacher team showed no mercy. One Friday, Rasheed decided to play on the kids’ team to show he was in their corner. He played quarterback like Michael Vick, scrambling around the pocket, throwing deep, drawing up plays in the dirt. The teachers won. But the score was closer than it had ever been before.

“ If a higher power had marked him to live out the plot of a movie, maybe he hadn’t been assigned Jerry Maguire.”

Here was a moment where Rasheed’s ideas and self-image could’ve shifted. If a higher power had marked him to live out the plot of a movie, maybe he hadn’t been assigned Jerry Maguire. Instead, maybe his film was Dead Poets Society, or Stand and Deliver.

Finals of the 2018 Pro-Am. People, like lava, spilled out of the doors of a jam-packed Stratford High School gym. Fans without seats stood all around the court. Each summer, the league had gotten a little bigger. Each year, Rasheed’s Rolodex had grown a little fatter. By 2018, Rasheed had, through sheer force of personality, become friends with Lou Williams, Mookie Betts, John Jenkins, and Chance the Rapper.

As tipoff approached, the energy in the gym crescendoed. The UniverSoul Circus would’ve been proud of the production value. That night, six current, former, or future NBA players shared the court. The crowd reserved its biggest cheers for Darius Garland, a local 18-year-old heading to Vanderbilt in the fall. The whole summer, he’d dazzled them with an array of crossovers, stepbacks, and sleights of hand. He was a high schooler, playing with and against NBA starters. It was obvious to the crowd that he was the best player on the floor. Less than four years later, in February 2022, he would become an NBA All-Star.

Before tipoff, Jeff McGruder looked around. Here he was, in his old high school, the same place that had seen gang wars and drug deals. His senior year, after a fight between the Bottom Boys and South Six, someone called in a bomb threat. During the evacuation, a few kids went to the nearby trails and grabbed some horses. Jeff still remembers kids on horseback, chasing their teachers across the front lawn.

Now, in that same place, pictures of his old team, which won the district and regional championships, hung from the walls. The stands overflowed, packed with kids who could be on corners anywhere in the city. Instead, they were here, junk food in hand, music on the speakers, watching the best athletes in the city play for free.

We’re here forever, Jeff thought. This will be around until I’m dead and gone.

In the years since high school, Jeff had grown up and earned multiple degrees. As an adult, he moves between worlds with the ease of a former college basketball player with an MBA. His hair is close-cropped, his beard is trimmed, he is tall and lean and handsome, his polos and slacks look tailored without being tailored. He still carries the physique of a D-I athlete thanks to 5 A.M. pickup games at the Downtown Y. Disciplined, optimized energy surrounds him, the air of someone who reads a lot of Malcolm Gladwell and has 500+ connections on LinkedIn. Returning to his old gym, he slid into handshake routines, checked on people, rained threes in Jordan Ones, his stroke pure as it ever was, his East Nashville roots strong as they ever were.

Meanwhile, Rasheed worked the sideline, wearing a custom throwback jersey. His dad and brothers sat in the “Gucci Row,” front and center, just off the scorer’s table. His mom sold concessions in the lobby. He strode into conversations, gave and received dap, ensured that his people were having a good time. As much as Darius Garland, he was the star of the Nashville Pro-Am. He was owning his moment.

“I was his mentor,” Jeff says. “But he was the face. It was his league, it was his dream. And that was awesome. It was perfect.”

Like his mother, gift-giving was Rasheed’s love language. And the Pro-Am was the gift he gave to his hometown.

As the Pro-Am continued to grow, Rasheed started to message Kerrisha Wilkerson on Instagram. The two technically didn’t know each other, but they ran in overlapping circles. At first, Kerrisha didn’t pay Rasheed much attention. She thought he was good-looking but too popular, too much of a celebrity. Rasheed persisted, and they started dating in August 2017.

Kerrisha expected Rasheed to be the way he acted on Instagram: flashy, entrepreneurial, a fountain of inspirational quotes. To some degree, he was. But over time, she realized that Rasheed’s social media persona was necessary for networking and running the Pro-Am. She loved who he was behind the scenes. The funny Rasheed, the daily Rasheed, the one who’d do anything for his people – that’s who Kerrisha admired. On his end, Rasheed felt like he’d found the ride-or-die he’d been missing in the hospital after the crash.

Like Rasheed, like Corisa, Kerrisha loves shoes. There's a pile at her door, and as she leaves the house, she pauses to choose the right ones for the occasion – Jordans, leather boots, Chucks, Nike Cortez.

Kerrisha has dark eyes and makes a lot of eye contact in a way that seems natural, not trained. When she looks at you, it's neither a challenge nor an invitation, nor a practiced habit of a highly effective person. When you meet her, you don't feel x-rayed, but rather grasped, comprehended, that she suffers no fools, that she's able to quickly analyze your character.

All relationships have their ups and downs, and theirs wasn’t perfect. Kerrisha had grown up with a dog and wanted one of her own. But whenever she asked Rasheed, he said no.

When Kerrisha and Rasheed got serious, she invited her cousins, Adrian and Tahmaj, and her little brother, KJ, to come meet him at Centennial Park. Those three boys are the last kids in the Wilkerson family, and Kerrisha saw them as her babies. Anyone who got close to her needed to vibe with them.

Rasheed brought a football, and he played quarterback while the boys ran routes against each other. At one point, he put too much heat on a pass and nailed KJ in the face.

“Why would you do that?” Kerrisha asked him, steaming mad.

“He’s a boy,” Rasheed shot back. “He’ll be fine.”

By sunset, as the lights switched on around the park’s lake, Rasheed had passed the test. He and the boys were already pouring into each other.

Kerrisha knew Adrian was a good kid. But as a teacher in Metro Nashville Public Schools, she’d seen plenty of good kids get into trouble. She knew how hard it was for modern, connected, tech-savvy 14-year-olds to avoid bad choices. After that afternoon in the park, Rasheed started picking Adrian up from school and taking him to the gym. Adrian was in 8th grade and struggled with his classes but dreamed of playing college basketball.

Adrian is naturally lean, with the kind of frame that all clothes look good on, but he’s built more like a soccer player than a small forward, more Neymar than Giannis. To play in high school and beyond, he needed to be skilled. Rasheed, who could always shoot, helped Adrian retool his jumper. “His form was perfect,” Adrian recalls. Then, Rasheed got him a real trainer. Rasheed told him that if he didn’t have good grades, basketball wouldn’t matter, since colleges wouldn’t give him a chance.

“Rasheed and Kerrisha named him Dallas Cowboy Walker. ”

Kerrisha loved Rasheed for his investment in her family. She also loved the little daily moments they shared. Drinking coffee together before they drove to work; talking on the phone; cooking dinner; watching TV. But what sealed the deal was when Rasheed asked her to run an errand.

He wanted Kerrisha to drive to Cookeville to pick up some shirts he’d ordered. She didn’t understand why she needed to drive an hour and a half for t-shirts. But she trusted Rasheed. Okay, she thought. Whatever.

When she pulled up to the address Rasheed had provided, a woman walked out, cradling a tiny bundle of fur in her arms.

Kerrisha was confused. “I’m here to get a box of shirts,” she told the woman.

“No,” the woman said, shaking her head. “You’re here to get a dog.”

Rasheed and Kerrisha named him Dallas Cowboy Walker. Even when he grew, Dallas was tiny, easily scooped up beneath one arm. He wasn’t the dog you would’ve immediately chosen for Rasheed, who so valued his masculinity. But he was the dog that Rasheed and Kerrisha loved, together.

The Nashville Pro-Am hit a high point in the summer of 2018, and the summer of 2019 was just as solid. Then COVID arrived, and in the summer of 2020, the Stratford gym went dark.

Idleness didn’t sit well with Rasheed. During the early pandemic, he began to feel stuck in place. In the fall of 2020, Rasheed had three important conversations. The first was with Dacari Middlebrooks, a friend he’d made at church. Faith had always provided a ballast in Corisa’s life, and her son was no different. Dacari and Rasheed shared a drive to discover their purpose in the world. They were both entrepreneurs, and they swapped books like The Alchemist and The Gucci Mane Guide to Greatness.

In November, Rasheed told Dacari that he worried about not knowing what was next. His twenties were already behind him. He knew he hadn’t yet reached the top of the Pro-Am space, and he still wasn’t a licensed teacher. He had complete confidence he would get there. He believed, but he felt the tiniest bit adrift, as though his life were still buffering. In his 30s, he was in a hurry to get to where he knew he could be. Even years on from the car crash, he wondered about his ultimate purpose.

The same month, Rasheed walked into K.C. Winfrey’s office at Cora Howe. He saw K.C. as a mentor and wanted to ask some big questions.

“Why don’t you hang the subbing thing up and get out there and pursue your dreams again?” K.C. asked him. He knew that Rasheed had always wanted to work in sports. Even though Rasheed was a big part of the school, K.C. felt like he was selling himself short as a sub.

When he relived the conversation over a year later, in the same office, K.C. felt he might’ve missed something by suggesting that Rasheed pursue sports. He could see in hindsight how everything Rasheed did was not about himself – but others.

“Him quarterbacking the kids team, his basketball league, and HUSTLEStrong – all of those things were about elevating kids,” he said.

A few days later, Rasheed bought suits from Dillard’s and lined up some job interviews in sports marketing. He also mulled over his future with Kerrisha. They’d been together for a while, and Dallas was like their child. Rasheed saw himself starting a family. He spoke to Kerrisha’s father and received his blessing to ask her to marry.

At 4:50 p.m. on Saturday, November 14, 2020, Rasheed arrived at the intersection of Dr. DB Todd Jr. Boulevard and Buchanan Street. He needed a haircut, and his brother, Benny III, ran his barbershop here. At golden hour on pretty days like this, Rasheed liked to hang out with a few friends in front of the shop, figuring out moves for the weekend. He wore a custom varsity jacket, red with white sleeves, dressed to go out.

On sunny days, this intersection feels collaged from other cities. Storefronts and railings are painted in pastels – red, yellow, blue, and cream – as if the designer dipped a brush into Havana. Around the block, people shop and eat, stopping to chat, moving at the familiar, unhurried pace of Angelenos. Music from Atlanta and Memphis – Migos, Future, Moneybagg Yo – rattles the old sedans that pass through.

But this intersection isn’t located in another city. This intersection is the hub of North Nashville. You know this is North Nashville because at the edges of your awareness, I-40 hums like a faraway chainsaw.

As Rasheed arrived at the barbershop, a black four-door sedan pulled up next to the Wireless Z store across the parking lot. A man jumped out, wearing a white long-sleeved t-shirt, a Chicago White Sox hat, and jeans. In his hands, he held a rifle. He opened fire, and Rasheed tried to run, but the bullets knocked him to the ground, face-first.

Benny III had just closed up shop and was taking out the trash when he heard the gunshots. He’d never seen the shooter before. He was armed, so he took cover and fired a shot at the man as he ran toward the sedan. The shooter jumped into the car’s passenger seat and sped away.

“Corisa began to cry. Benny held Rasheed’s hand. He kissed his youngest son on the head and left the room. ”

Rasheed’s brother ran back into the shop and called their dad. By the time Benny Jr. arrived, the police had roped off the area, and an ambulance had arrived on the scene. Rasheed lay on the asphalt, alive, bleeding. His father followed the ambulance to Vanderbilt Hospital, where five years earlier, Rasheed had survived eight surgeries.

Maybe they can save him, Benny thought. They’d done it once before.

At 10 p.m., doctors told Benny, Corisa, and Rasheed’s brothers to go home. They’d call with updates.

After midnight, Benny’s phone rang. “Come to the hospital,” the doctor said. When the family arrived, a nurse stepped out to address them. Rasheed was dying, she said. If they wanted to see him, the time was now.

Benny, his sons, and Corisa walked into Rasheed’s room. The nurse placed her stethoscope on Rasheed’s chest, then turned and looked at the family.

“He’s gone,” she said.

Corisa began to cry. Benny held Rasheed’s hand. He kissed his youngest son on the head and left the room. He took the elevator to the ground floor and walked out the hospital’s front doors. He crumpled to the curb, and he let his mind go.

Three weeks later, a 28-year-old man named Robert Rasean Smith was arrested. He was charged with criminal homicide, drug possession, and unlawful gun possession by a convicted felon. In May 2022, he took a plea deal, receiving a sentence of 44 years in prison for second-degree murder, for a random act of violence. Nobody has explained why he pulled the trigger.

July, 2021. At sunset, the air north of Nashville feels thick and still. Cars move slow and easy on a sepia-toned two-lane section of Old Hickory Boulevard, as if swimming through honey.

Even on this languid evening, hundreds of cars are parked at Davidson Academy. In the peak of Nashville’s summer, a high school gym has switched on its lights. Inside, voices shout, sneakers squeak, and tall men run up and down a basketball court, their shadows dancing across the polished wooden floor.

The crowd has shown up for the Finals of the 2021 Nashville Pro-Am Basketball League, which has returned after a year off due to COVID. The gym smells like sweat, candy, and hustle, and the game is competitive. The fans are content, at ease, leaning back against the rows of bleachers behind them.

Corisa works the lobby, where she sells concessions, operates the HUSTLEStrong table, and hands out wristbands. Seven months earlier, at Christmastime, Corisa decorated her Christmas tree with its usual intricate boughs and tinsels. She placed it in the center of her living room. Then, she put a second tree on a table in the corner. She decorated it with specific ornaments – a Cowboys helmet, a Bulls logo, a Kevin Garnett action figure. At the very top, she placed a silver letter “R.”

Corisa isn’t much for public emotion. She returned to work a few days after her son’s death, and at Rasheed’s funeral, she didn’t cry a single tear. Since Rasheed’s passing, she’s created a memorial scholarship in his name at Tuskegee, his alma mater. Everyone knew she was strong. Everyone also knew she’d lost half of her heart.

Kerrisha, Adrian, and Tahmaj sit in the Gucci Row, close to Benny. Since his son’s death, Benny has left the guest bedroom in his house, where Rasheed would occasionally spend the night, untouched. It has none of the curation of an Ofrenda, but rather the preserved quality of a museum, with several exhibits. The basketball hoop through the window, casting its shadow in the filtered sunlight of summer evenings. The single AirPod on the nightstand, missing its mate. The 55” Samsung TV on the dresser, on which Martin reruns used to flicker late at night. The closet full of Dillard’s suits, never worn, which Rasheed bought for job interviews, never attended.

Benny’s thoughts never stray far from his son. He passes Rasheed’s headstone every time he drives to the RiverGate mall.

At halftime, some kids trot out onto the court and start shooting around. After a few moments, Jeff McGruder joins them, knocking down straightaway threes in his red Jordan Ones.

There’s an easy, timeless summer feel to everything happening in the gym. There’s also a weight in the air that has nothing to do with the heat. After he shoots for a few minutes, Jeff grabs the microphone from the scorer’s table and walks to center court. The gym goes silent. Without his partner, his mentee, Jeff is now the only one in charge. It’s his job to say what everyone is thinking.

“I don’t want to forget why we’re here,” Jeff says into the mic. “And that’s for the mission of a man we lost.”

The crowd nods.

Rasheed isn’t physically here, but what’s happening in this gym is proof of his life. There aren’t any NBA players in the league this year, because Rasheed was the one with those connections. But local college players are shining in their place. Teenagers who could be on any corner in Nashville have chosen to be here, junk food in hand, watching the best athletes in the city play for free. There’s buzz – unsubstantiated, but who knows? – that next season, Ja Morant of the Memphis Grizzlies might pull up. Even after a global pandemic, even after Rasheed’s death, the Pro-Am is one of Nashville’s rites of summer.

Jeff asks the crowd to bow their heads. After a long moment, he raises one fist to the sky. “Hustle on three!” He yells. “One…two…three!”

“Hustle!” The crowd screams back.

And then, the game goes on.

Depending on how they knew him, people around town talk about two distinct Rasheed Walkers. There’s the Rasheed who hung out with Lou Williams, PacMan Jones, and Chance the Rapper, the man who could show up at NBA All-Star Weekend and walk away with a meeting with Adam Silver. The Rasheed who wore Jordans and throwbacks.

There’s also the Rasheed who created a handshake with Jake, played football with students at Cora Howe, and gave his clothes to kids in Soweto. The Rasheed who adopted Adrian, Tahmaj, and KJ as little brothers and loved quiet morning coffees with Kerrisha and Dallas. Rasheed the serial entrepreneur; Rasheed the humble educator.

People around Nashville felt Rasheed was on the cusp of something big, bigger even than the Pro-Am. Some said he would’ve moved away from his hometown to get there. Others thought he never could’ve left his mother. Maybe he would’ve started a sports agency, or at least represented an athlete he knew. Maybe he would’ve brought an NBA team to Nashville. Some folks think the tragedy at the heart of Rasheed’s story is that he was just about to become the fullest expression of himself. He was next up in Nashville’s long lineage of Black excellence, co-signed by community fixtures like Jeff. He was going to be special.

When he died, he still had big wants yet to achieve. But Rasheed Walker already was special. He already was doing something big. He was inspiring kids in Nashville to be better.

It’s easy to deify Rasheed. But he was also a regular person, with normal insecurities. He didn’t know what was next. He felt he was still in search of his purpose. What made him special was the way he chose to live. He decided to serve others, to teach kids to never give up.

After Rasheed died, Adrian, Kerrisha’s cousin, almost quit playing basketball. Rasheed was the one who’d pushed him, who’d fixed his jumper. Rasheed was among the main reasons he’d stuck with basketball in high school. During Adrian’s junior season in 2021, Kerrisha showed up to the gym to support him as much as she could. “I’m just not feeling it,” he sometimes told her. “I’m not into it. I look over to the bleachers and I don’t see what I used to see.”

“If he was here,” Kerrisha asked, “what do you think he would tell you?”

Heading into his senior year, Adrian ended up sticking with the team at East Nashville Magnet, Kerrisha’s alma mater. He’d played with half his teammates since middle school, and he didn’t want to bail on them. This year, the team clicked like never before. They flew around the court, pressed opponents into submission, and rained threes from near NBA range. Everything they did dripped with swagger. They entered the state tournament in March with 30 wins and three losses.

“Throughout the season, Adrian saw traces of Rasheed everywhere.”

Throughout the season, Adrian saw traces of Rasheed everywhere. On the court, whenever he shot a three with the textbook form Rasheed taught him. In his closet, where gifts from Rasheed proudly hung: a Jordan jersey, a St. Vincent’s/St. Mary’s LeBron jersey, a Nashville Pro-Am jersey, which he plans to get framed. At Kerrisha’s apartment, when he and Tahmaj headed over to play with Dallas.

At state in Murfreesboro, the East Nashville Eagles were undeniable, cruising through each opponent, winning the finals by 17. When the announcer proclaimed them state champions, Adrian and his teammates Griddied to center court to accept their trophy, their golden ball. Adrian beamed, still waiting for his braces to come off, wearing the kind of smile that had become rarer and rarer since November 14, 2020.

Like Rasheed, Adrian is undersized, standing 5’10”. Some of his teammates have multiple college offers, and Adrian doesn’t – yet. But because of Rasheed, he has the grades. His jumper is pure. And he isn’t giving up.

Maybe someday, he’ll play in the Nashville Pro-Am.